The Bullet Cluster is frequently cited as evidence against MOND, with some even claiming it definitively disproves the theory. Such arguments often stem from a misunderstanding of what MOND actually is. This misconception is not confined to online debates either; it can also be found in the scientific literature. For instance, in Dark Matter and Dark Energy: A Challenge for Modern Cosmology (2011), Matarrese et al. critique a fictitious MOND strawman in their discussion of the Bullet Cluster (as in they actually don’t understand the math).

In this post, we will examine the widely accepted Bullet Cluster narrative, provide a counterexample, look at what MOND actually says about this cluster, and evaluate whether the Bullet Cluster truly poses a challenge to the theory. This article is the first of two articles on clusters and MOND. Hopefully by the end of post two you’ll agree that “the lensing signal of the Bullet Cluster proves MOND wrong” is not a good argument whereas “clusters don’t follow the radial acceleration relation so MOND is wrong” is the far stronger argument.

The dark matter story

The basic dark matter story about the Bullet Cluster usually goes as follows:

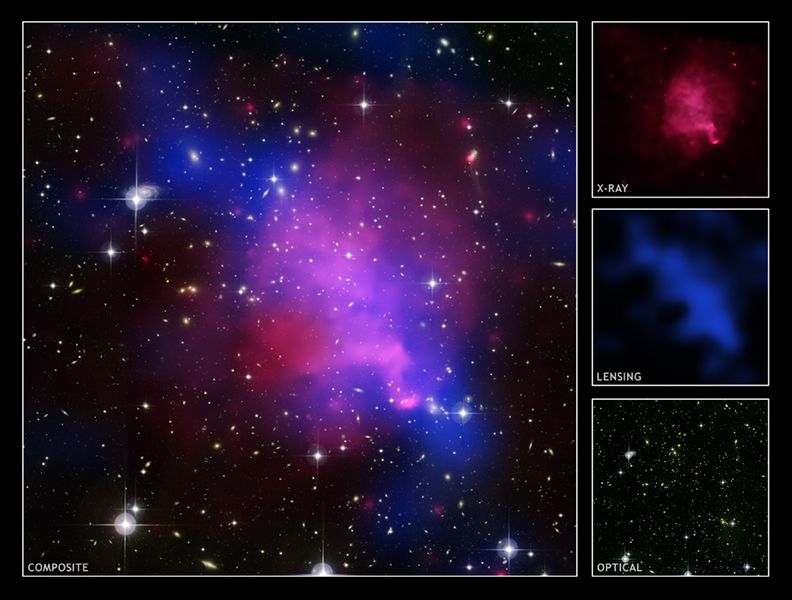

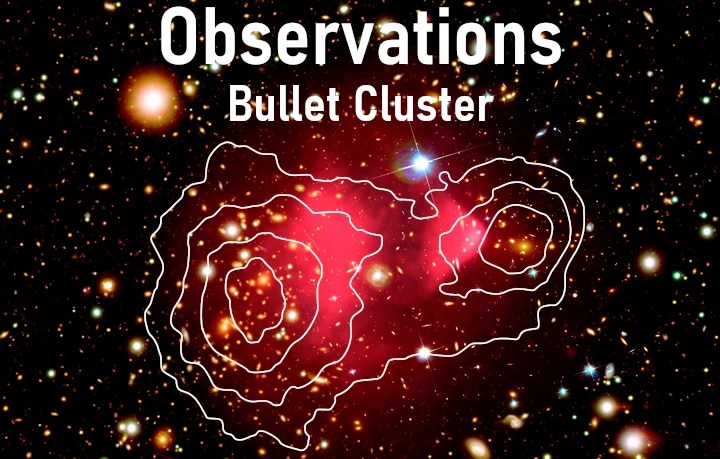

This composite image [see below] shows the galaxy cluster 1E 0657-56, also known as the “bullet cluster”, formed after the collision of two large clusters of galaxies. Hot gas detected by Chandra is seen as two pink clumps in the image and contains most of the “normal” matter in the two clusters. An optical image from Magellan and the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies in orange and white. The blue clumps show where most of the mass in the clusters is found, using a technique known as gravitational lensing. Most of the matter in the clusters (blue) is clearly separate from the normal matter (pink), giving direct evidence that nearly all of the matter in the clusters is dark. This result cannot be explained by modifying the laws of gravity.

And that’s pretty much the whole argument. Modified gravity can’t do that. Well the people who work on modified gravity beg to differ. This story was first published in the rather presumptuously titled “A Direct Empirical Proof of the Existence of Dark Matter“. It became immensely popular with well over 4000 citations. Yet that paper doesn’t even attempt to analyse the Bullet Cluster using MOND. In fact since then the Bullet Cluster has been analysed using MOND and the conclusions are rather different.

As we can see in 2. What is MOND? The additional “mass” (i.e. the region where gravity is modified and the interpolation function is larger than 1) does not align perfectly with the distribution of actual mass. In regions of dense matter, gravitational acceleration is high, and no modification to Newtonian mechanics is expected. Conversely, in low-density regions with weak gravitational accelerations, the interpolation function becomes large. When examining the data, this is precisely what we observe in the Bullet Cluster. Most of the ordinary mass is in the hot X-ray gas (pink), which is densely concentrated. Such gas typically experiences relatively strong gravitational fields compared to a0 and the collision compressed it even further. As a result, the gravitational field is strong in these regions, and MOND does not significantly enhance gravity here. In contrast, the galaxies—containing most of the stellar mass—are spread out a lot and have less mass than the gas. There the gravitational field is very weak. So between the galaxies, MOND significantly boosts the gravitational effects.

In short the additional gravity occurs in low acceleration regions and not per se where most of the mass is. Qualitatively at least the Bullet Cluster makes perfect sense in MOND.

This is a fundamental feature of MOND and is outlined in the introductory sections of any serious paper on the subject. Anyone using the Bullet Cluster as an argument against MOND simply misunderstands the theory. If this applies to you, thanks for taking the time to read up on the annoying upstart competition that just won’t die. While MOND does face challenges when applied to galaxy clusters, as we will explore later in this post and the next, the narrative outlined above is simply incorrect.

The Trainwreck Cluster

The reason the Bullet Cluster narrative is so appealing is that it seems to highlight a key feature of dark matter: its collisionless nature. Dark matter particles are believed to interact with ordinary matter and with themselves only through gravity, or at most extremely weakly through other forces. This property is crucial; otherwise, dark matter would be detectable through other means. Which it hasn’t been. According to dark matter theory, when the two subclusters of the Bullet Cluster slammed into each other, the dark matter—like the galaxies—passed straight through and emerged on the other side. Thus, the observation that the lensing and inferred dark mass are strongest near the galaxies aligns with this view. But the Bullet Cluster isn’t the only cluster collision out there. Enter Abel 520, better known as the Trainwreck Cluster.

Here the lensing shows the exact opposite pattern as the Bullet Cluster. The lensing and hence purportedly the dark matter is the strongest in the middle. That doesn’t make sense if there really is collisionless dark matter out there.

Just because the opposition is making an incorrect argument doesn’t make MOND right of course! So let’s look at the Bullet Cluster using MOND more quantitatively.

The Bullet Cluster in MOND

Earlier in this post, I noted that the original claims about the Bullet Cluster did not even attempt to model it using MOND. To date, there have only been two studies that consider the Bullet Cluster in the context of MOND. One of these studies employs a relativistic extension of MOND known as TeVeS, which has since been ruled out by the gravitational wave event GW170817.

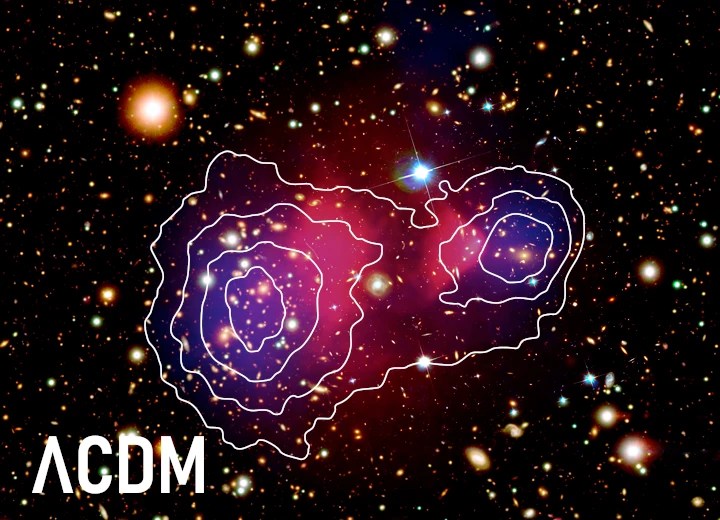

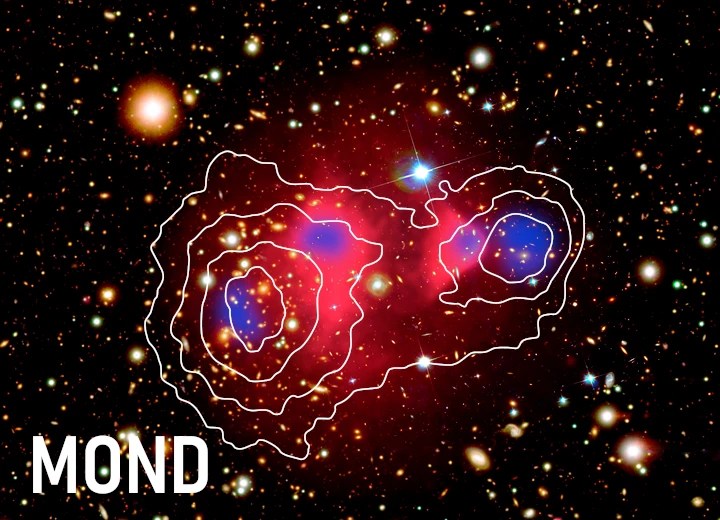

Which leaves us this study of the Bullet Cluster using MOND. The results of this study are illustrated in the image below, using the same color scheme as the earlier dark matter analysis. Stars and galaxies are depicted in white and orange, while the hot X-ray gas appears in pink. The white lines indicate the gravitational field as inferred from gravitational lensing. The blue regions highlight four areas where MOND predicts slightly more mass than has been observed to date.

Aha so MOND fails the Bullet Cluster after all!

Well MOND mostly gets it right and this additional mass it expects could simply really be there in a way that is hard to see. That sounds like dark matter though right? And the entire point of modifying gravity is not to need any dark matter. So this isn’t a good look. But the missing mass could just be ordinary baryonic matter that has not been detected yet— that has happened before. When Zwicky first studied galaxy clusters, he was unaware of the hot X-ray-emitting gas, as it had not been discovered yet. Since this gas constitutes the majority of the baryonic mass in clusters, Zwicky concluded that far more dark matter was needed than even modern theories suggest. Milgrom suggests hard to detect cold dense nuggets of hydrogen may be the culprit. The additional mass required is small enough not to be ruled out by Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) either. But given the high temperatures and the absence of cooling flows in clusters — due to AGN feedback — the existence of such cold hydrogen gas is unlikely.

The Cluster Conundrum

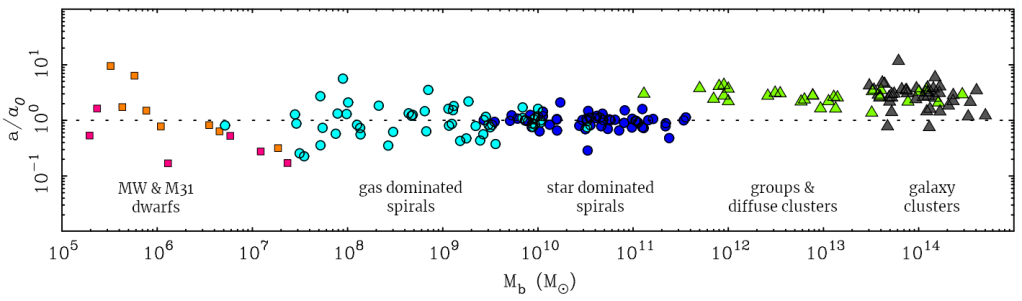

So was all of that a longwinded way of saying MOND fails anyway? Not quite. While the conventional anti-MOND narrative is certainly flawed, MOND does appear to require slightly more mass than has been observed thus far. That could be undetected baryons. However, there is another possibility, supported by a broad range of evidence: a systematic bias in the analyses of X-ray emitting systems:

From the MOND perspective, this seems to be the most promising explanation. All X-ray-emitting systems deviate from MOND predictions by up to a factor of 2, yet qualitatively, the data still closely resemble what MOND would predict.

For the full story about this continue reading in the next post in this series:

27. Clusters Part 2: What is the MOND Cluster Conundrum?

There we will also circle back to the Bullet Cluster after we’ve laid some more groundwork.

Further reading

If you are interested in reading more on the Bullet Cluster and MOND the following three posts on professor Kroupa’s blog

Finally there are also some links on the Bullet Cluster over on Stacy McGaugh’s MOND Pages.

Leave a Reply