In post two of this series we’ve seen how MOND has two main gravitational regimes, the Newtonian and Milgromian (or Deep-MOND) regimes. These regimes are connected to each other using an interpolation function. The acceleration at which the two regimes connect is Milgrom’s constant a0 at 1.2*10-10 m/s2. However as I’ve alluded to in post two, there are in fact two more regimes to consider in Milgromian dynamics. These two regimes, the quasi-Newtonian regime and the forced Newtonian regime, are the topic of this post and are collectively known in the literature as the “external field effect” (ExFE or EFE).

The external field effect is not the tidal force.

The ExFE is unique to Milgromian dynamics and occurs when a system is embedded in the external gravitational field of a larger host system. This is often confused with the well known phenomenon of tides and the two may occur simultaneously. Tides occur when a non-uniform external gravitational field encompasses an object causing it to be stretched and squished. In Newtonian gravity a system is completely unaffected by external fields as long as those external fields are uniform. In Milgromian dynamics this is not (always) the case. In Milgromian dynamics even uniform external fields may have an impact because they can change the value of the interpolation function at that particular location. This is because the interpolation function always applies only to the total gravitational field at any particular location.

How to account for tides in Milgromian dynamics will be the topic of the next post in this series. This post first describes the four limits of MOND, two of which are due to the external field effect, then shows how one can account for the ExFE to a first approximation and then covers the evidence for the ExFE that’s currently available.

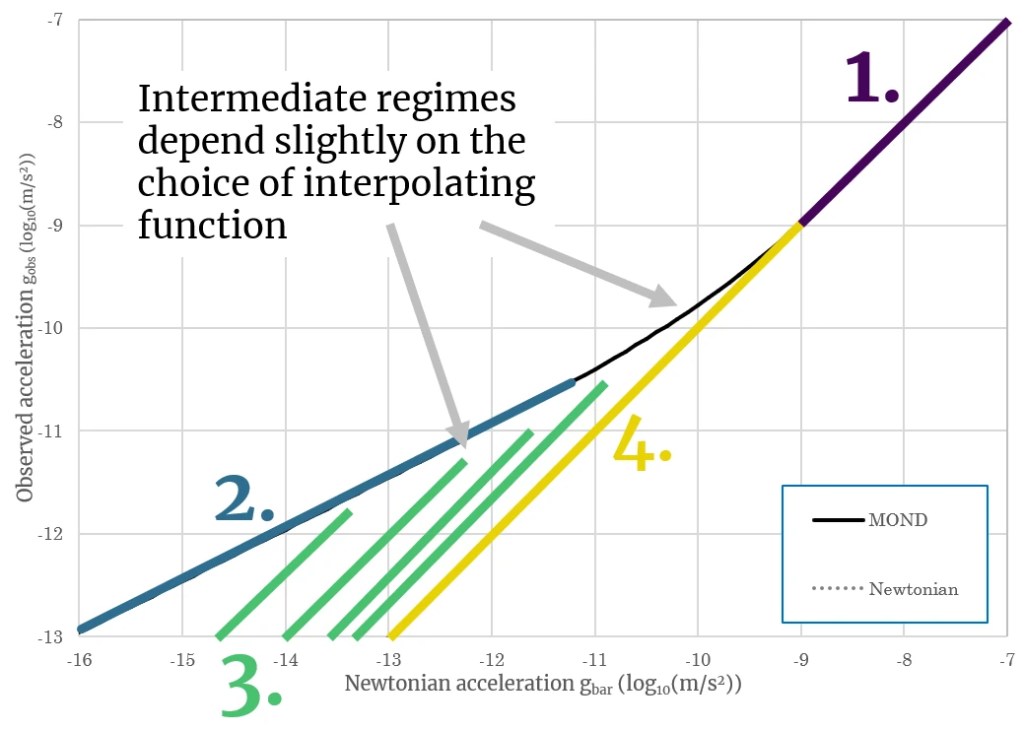

Overview of the four limits in Milgromian dynamics

In the rest of this article the symbols a and g both denote accelerations. The subscripts int and ext both denote the ordinary gravitational acceleration as Newton would calculate them for the system’s own gravitational field and the external field acting on it respectively.

1. The Newtonian limit

This occurs when the internal gravitational field present in the system is stronger Milgrom’s constant a0. In this case there is no external field effect. The system is isolated so far as the external field effect is concerned though there may still be ordinary tides. The orbits of the planets in the solar system are in this regime governed. This limit has been covered in the post 2. What is MOND? so won’t be covered further here.

2. The Milgromian limit (Deep-MOND limit)

This occurs when the internal accelerations are lower than Milgrom’s constant and is isolated from external fields. The outer edges of galaxies are often in this limit which is why rotation curves become flat. Same as for the Newtonian limit, see: 2. What is MOND?

3. The quasi-Newtonian limit

This occurs when the internal gravitational field and the external gravitational field are both smaller than Milgrom’s constant but the external gravitational field is stronger than the internal field. In this case the interpolation function is constant. As a consequence the system behaves very similar to a Newtonian system, with falling Keplerian rotation curves or velocity dispersions. The difference is that there is a constant boost of the gravity compared to the pure Newtonian case. This is often represented in the MOND literature as a Newtonian system with a rescaled Newton’s constant (Newton’s constant multiplied by the interpolation function). In terms of dark matter theory these systems could be inferred to have dark matter but all of the dark matter is centrally located in a single point instead of in a halo (the latter of which would be required to fit data in the Milgromian limit).

4. The forced Newtonian limit

This limit of MOND gives us the second regime where the external field effect applies. For systems that are embedded in external fields that are (considerably) stronger than a0, all internal accelerations are forced to be Newtonian. This is because the interpolation function equals 1 because it is determined by the total gravitational field which in this case is much larger than a0. The forced Newtonian limit is distinct from the quasi-Newtonian limit because there is no detectable difference from ordinary Newtonian dynamics that can be measured here locally. In terms of dark matter theory, the system would be inferred to lack any dark matter, or be in a completely uniform dark matter distribution. For earthbound measurements of this regime see: 19. Do laboratory tests rule out MOND?

Accounting for the ExFE to a first approximation

One can account for the external field effect with the following first order approximation:

This approximation does assume that the system in question is spherical, the external field is uniform and that the direction of observations of the internal gravitational acceleration and the external gravitational field are the same. This simplification prevents the need for detailed numerical modelling of the system using ad hoc empirical interpolation functions, it does however overestimate the influence of the external field effect slightly (up to ~10%).

Evidence for the external field effect

There are several lines of evidence supporting the existence of the external field effect. Because the ExFE is rather fundamental to a lot of problems these lines of evidence are described in detail in separate articles. Below follows a summary with links to further reading on each:

- Theoretical consistency

The external field effect is a theoretical consequence of most formulations of the MOND field equations. It is necessary to get the same results for an analysis of a system as a whole or for its parts. More on this can be found in this post:

10. Does MOND violate conservation laws? - Laboratory experiments

Some of the strongest evidence for the external field effect comes from laboratory measurements on Earth. These reach very small accelerations on the order of 0.001 times a0 and the results are consistent with the expected forced Newtonian limit. More on this can be found in this post:

19. Do laboratory tests rule out MOND? - Dwarf satellite galaxies

Dwarf satellite galaxies can be found orbiting around most major galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda. They are small systems with very low internal gravitational accelerations and consist of somewhere between a thousands and a billion stars. These dwarfs are embedded in the gravitational field of their host galaxy and seem to be affected by both the external field effect and tidal forces. More on this can be found in this post:

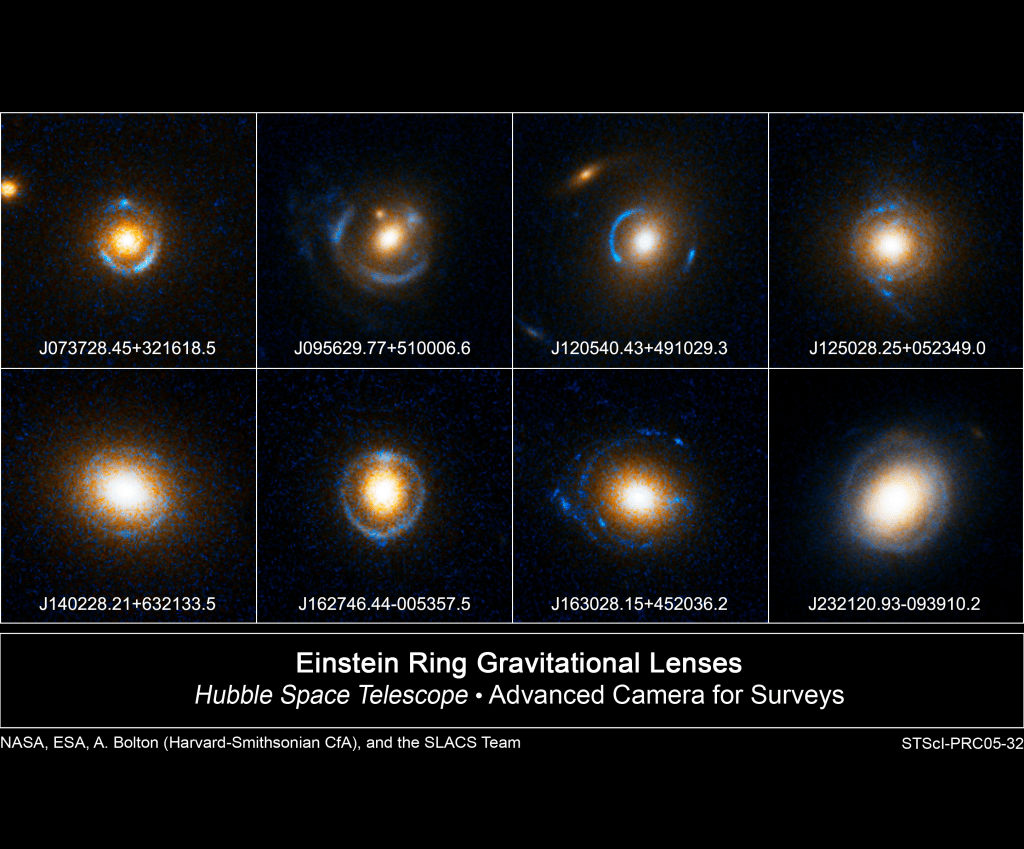

22. Do dwarf galaxies disprove MOND? - Lyman-alpha forest

Light from quasars in the early universe that shines through clouds of hydrogen show a very distinct spectral signature which allows astronomers to deduce various properties about these hydrogen clouds such as density and size. Reasonable estimates show that the observed sizes of these systems do not match the Deep-MOND regime but are not fully Newtonian either, matching best with the quasi-Newtonian regime due to the external gravitational fields of the large scale structure of the universe. See the first half of this paper. - Tidal tails

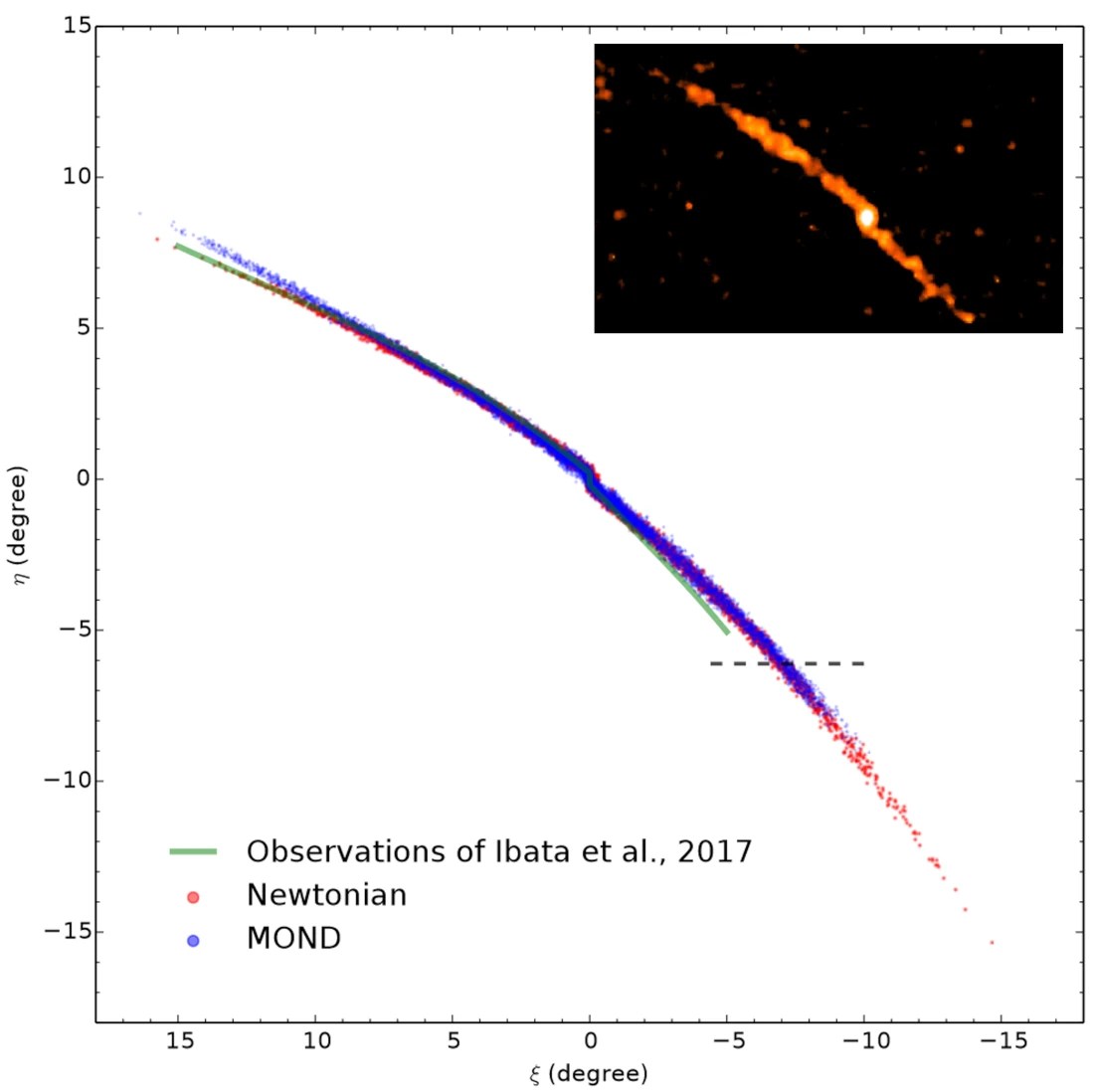

Open clusters and globular clusters with tidal tails in the external field of the Milky way are asymmetric as they are being ripped apart. The leading tail is longer than the trailing tail. In Newtonian gravity without the external field effect we would expect the tidal tails to be symmetric. This is a case where both tidal forces and the external field effect occur simultaneously. See for example this case of Palomar 5:

- Wide binaries

Two independent groups led by professor Chae and professor Hernandez have shown that wide binary star systems show clear evidence of Milgromian dynamics. Wide binary stars are stars that are orbiting each other at such a great distance that their mutual gravitational attraction shows a MOND like boost in gravitational strength. Because these star systems are embedded in the gravitational field of the Milky Way, these systems are expected to be in the quasi-Newtonian regime. The observational evidence seems to support this aspect of MOND. There is another researcher who disagrees but his methodology is severely flawed. More on this in the following MOND FAQ post:

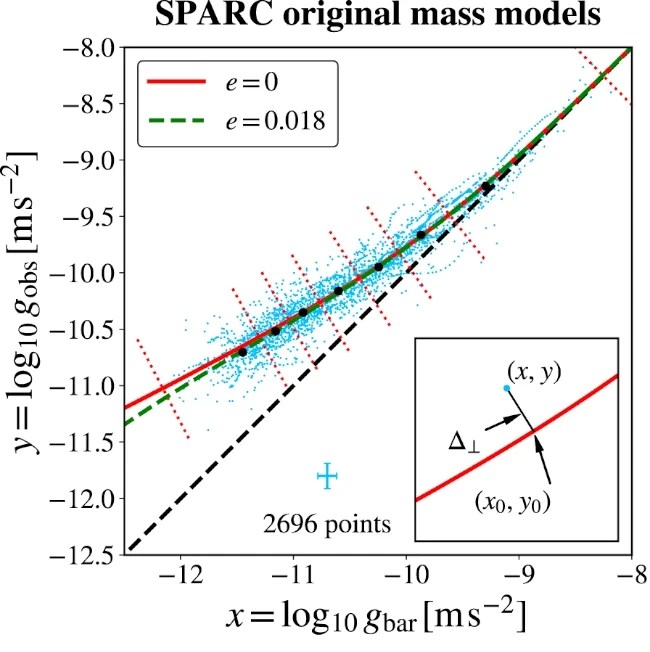

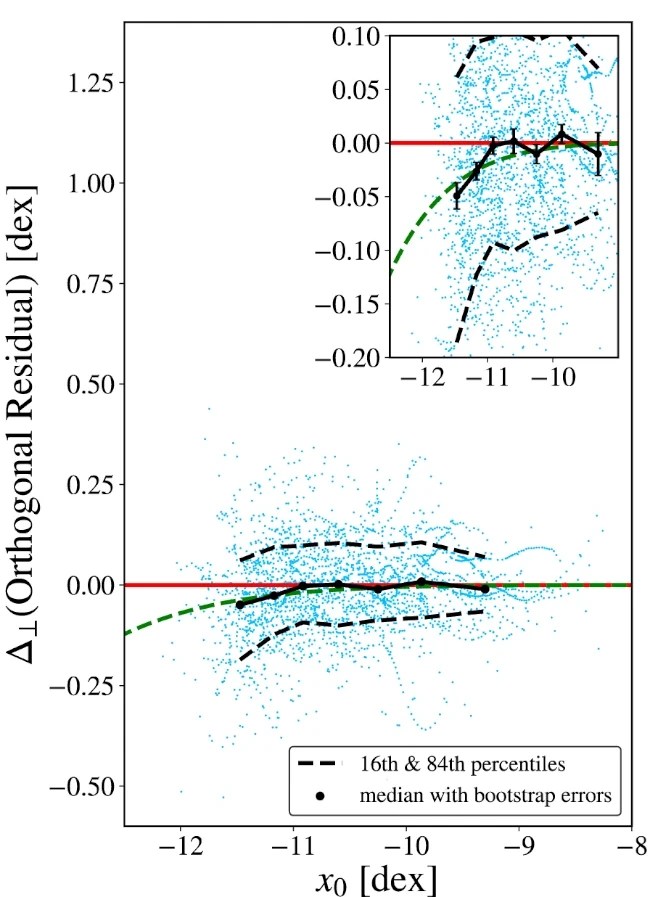

25. Do wide binary stars prove or disprove MOND? - SPARC Rotation curves

Chae et al. also analysed rotation curves of galaxies in the SPARC database and found a small but very significant decline in the furthest reaches of galactic rotation curves, right around the acceleration where we would expect the gravitational field of the large scale structure of the universe to become comparable to the gravitational field of the galaxy itself. This signifies a transition from the Milgromian regime of MOND to the quasi-Newtonian regime. Stacy McGaugh over at Triton Station has already covered that in far better detail than I can do here so I’ll just post the plot that I found the most impressive and the link to his take on this particular result below.

Leave a reply to 8. Does MOND violate equivalence? – Continental Hotspot Cancel reply