A poignant question one may ask that is strongly related to the previous post is can MOND do cosmology yet? After all the field of precision cosmology and the highly successful LCDM1 on which it rests have heaps of high quality datasets which MOND would have to fit if it is ever going to replace LCDM. So far, no, this is still a far off prospect.

Of course a similar question can be asked of LCDM. Can LCDM do correct a priori predictions2 of rotation curves yet? The answer to that question is similarly, no. There is a fair amount of mutual incommensurability between LCDM and MOND.

So no, MOND as classically proposed by Milgrom and Bekenstein can’t do CMB powerspectra, the matter powerspectrum or match the full Hubble diagram.

Some progress has been made in recent years however. Perhaps the most promising relativistic MOND theory currently is Aether Scalar Tensor (AeST) theory, (previously also called RelMOND) which claims to be able to fit the CMB power spectrum and give correct fits to large scale structure formation while simultaneously giving MOND behaviour on small scales. AeST requires additional fields however much like GR requires dark matter to fit all the observations. Its CMB fit is also not nearly as precise as that of the Planck collaboration using LCDM (the error bars are very small even if both plots look satisfying).

AeST has been covered in considerable detail over on Triton Station so I won’t belabour it here:

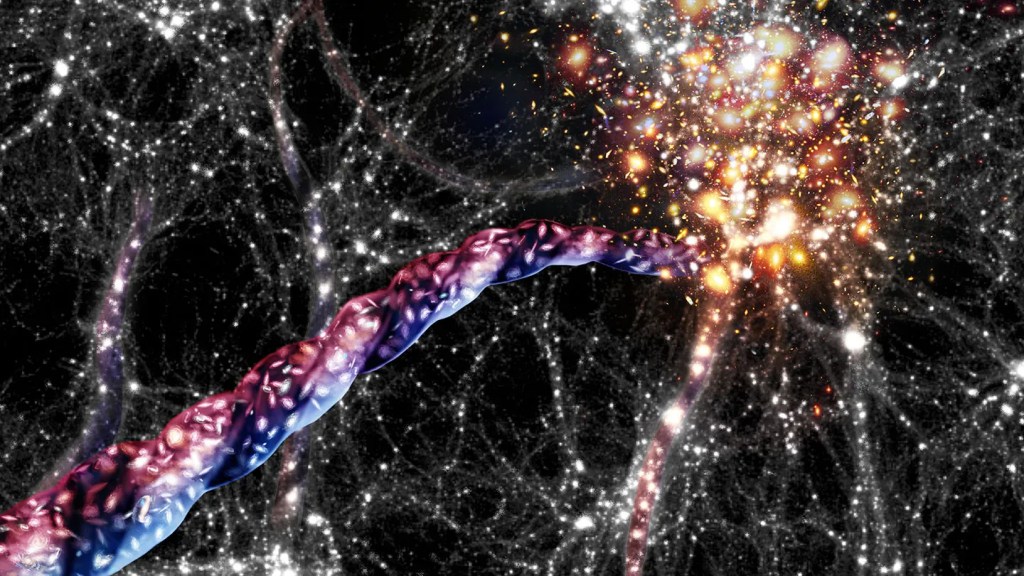

Cosmic filaments

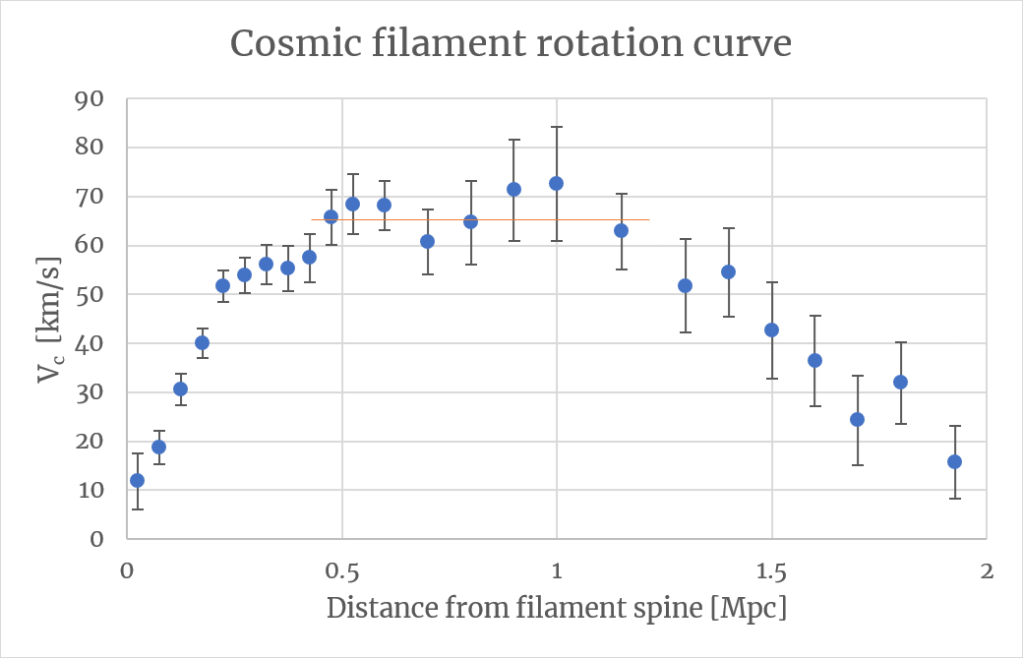

Cosmic filaments deserve a bit more treatment however because here MOND may soon be knocking on the door of cosmology with observations from its native repertoire. Three years ago now Wang et al. (2021) published a first of its kind rotation curve for cold cosmic filaments by measuring galaxy peculiar velocities relative to cosmic filament spines. Their final fiducial sample consists of 17,181 filaments, and 213,625 galaxies in total with a mean redshift of 0.085. I have reproduced this curve below, averaging the approaching and receding side of the rotation curve and doubling the bin size beyond 0.5Mpc yielding the following smooth curve:

From a MOND perspective we can make several interesting deductions from this rotation curve. As is expected by MOND for low density systems we see that the rotation curve rises gently and flattens out (indicated by the red line). It then stays flat for another 0.75 Mpc. As explained by Milgrom (1983b) this shape qualitatively means that the filament out to 1.2 Mpc is in the isolated Deep-MOND regime with internal baryonic accelerations below a0. In the rising part the cumulative mass increases until basically almost all of the mass is within that given radius after which it flattens. This qualitative picture matches with the observed dynamic accelerations which can be quantified by gobs=V2/R and range from 10-12.7 to 10-13 m/s2. If this reading of the cosmic filament rotation curve is correct we can apply the limit of the Deep-MOND regime to calculate the baryonic acceleration from the dynamic acceleration and predict the location of filaments on the radial acceleration relation out to 1.2 Mpc.

Of course no system in the universe is ever truly isolated and rotation curves that stay flat eventually do start declining due to the external field effect as they enter the quasi-Newtonian regime. We may see this happening after 1.2 Mpc. In this regime the value of the interpolation function stays constant as it is set by the strength of the uniform external field which dominates the total gravitational field strength. The value of the interpolation function at the final point of the flat regime also corresponds very roughly to the value that holds for the entire quasi-Newtonian regime. By taking this value and applying the quasi-Newtonian limit to the remaining dynamical accelerations we can determine the complete position of cold filaments on the radial acceleration relation:

It should be noted that this rotation curve is based on a sample of “cold” filaments in which the velocity dispersion is small compared to the circular velocity so we don’t need to worry about including an additional acceleration term to the dynamic acceleration for pressure supported motion. The qualitative reasoning above also assumes virial equilibrium which too is validated by only using cold filaments. Filaments in which galaxies are collapsing rapidly towards the spine would show a high velocity dispersion compared to rotation and be considered “hot” because on either side of the spine there would be movement towards and away from us towards the spine.

So far no direct measurements of the baryonic mass of cosmic filaments exists with which we can check if the qualitative reasoning above is correct. The WHIM is very faint and many filaments have to be stacked to detect it. This has been done for lensing and tSZ data Tanimura (2020a), for archival X-ray data Tanimura (2020b) and with early calibration X-ray data from SRG/eROSITA Tanimura (2022) but so far these datasets lack the resolution necessary to pair it with the rotation curve presented above. This may soon change with the first main data release from SRG/eROSITA earlier this year. Exciting data awaits us!

Cosmic filaments may become a problem for LCDM

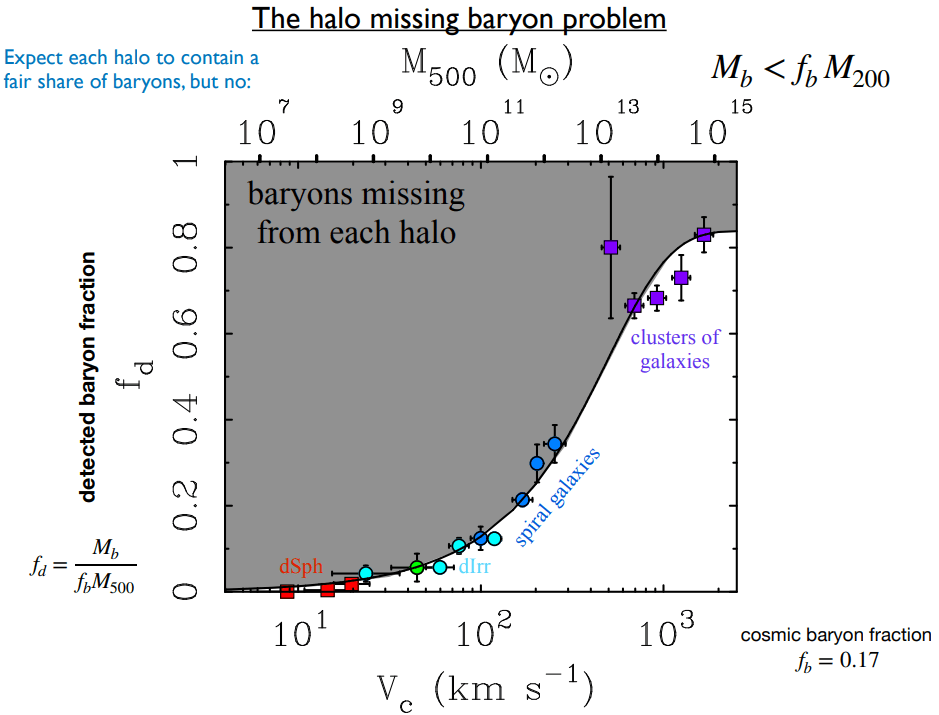

If the qualitative reasoning about cosmic filament rotation curves holds up this would be rather problematic for LCDM. Key pillars of LCDM are the CMB and BBN both of which predict there must be a given amount of baryonic matter compared to dark matter. On smaller scales from dwarf galaxies to galaxy clusters too little normal baryonic matter is detected compared to this LCDM prediction.

This (halo by halo) missing baryon problem is usually explained by feedback from supernovae and AGNs blowing baryonic matter out into the intergalactic medium. Therefore the warm hot intergalactic medium as present in cosmic filaments should be somewhat enriched in baryons. After all the feedbacked normal matter has to go somewhere.

If the qualitative reasoning above based on the rotation curve is correct we will find the opposite. From a dark matter perspective one would interpret the value of the interpolation function as the ratio of normal matter to dark matter. Because of the extremely low accelerations in filaments the value of the interpolation function is very high on the order of 100-1000x. This would put cosmic filaments somewhere between gas dominated galaxies and dwarf spheroidal galaxies in terms of the detected baryon fraction. Early results from Tanimura (2020a) have detected less than a tenth of the cosmic baryon fraction in filaments. This is not at all what we would expect from LCDM unless one posits that baryons are feedbacked all the way into the voids between filaments.

^1 This lead was originally a paragraph in the previous post and a commenter asked why anyone would think that LCDM is “highly successful” given the evidence against it (from for example dynamical friction). Well because LCDM just is very successful. Anyone who denies that is overly partisan. Even if eventually the consensus becomes that it isn’t a good description of fundamental reality it is still a very good fitting function for cosmological datasets. It has only half a dozen free parameters yet it contains a great deal of explanatory power. For example using LCDM one could calculate the polarization of the CMB from its power spectrum and vice versa. Or use the CMB to predict the BAO peak in the clustering correlation function. In this way LCDM makes other measurements possible such as Brouwer’s weak lensing RAR (based on the WMAP 9-year LCDM cosmological parameters).

^2 It has become so common in cosmology to use “prediction” and “fit after the fact” interchangeably that this is actually a necessary distinction.

Leave a reply to BoredObs Cancel reply