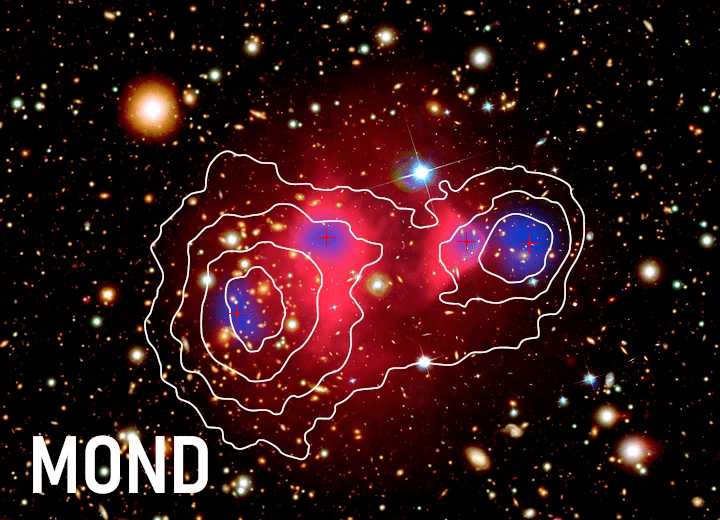

Galaxy clusters are among the most enigmatic objects in the universe, raising fundamental questions about the nature of reality. Could they be filled with vast quantities of mysterious, as-yet-undiscovered dark matter? Even Milgrom’s Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), a new theory of gravity, struggles to explain these colossal assemblies of gas and galaxies. In this post, we’ll explore why galaxy clusters are challenging for MOND, distill the available data into a set of rules to better define the problem, and indulge in some speculative ideas about its possible cause.

Contents

- Introduction

- MOND falsified?

- Are large systems different?

- Are spherical systems different?

- Elliptical galaxies as mini-clusters

- Galaxy clusters examined

- Regularities

- Speculation time!

- Xray analysis basics

- Unaccounted for pressure

- Estimating the nonthermal pressure fraction

- The Bullet Cluster again

- Summary

- What’s next?

- References

Introduction

In case you are not familiar with MOND (aka Milgromian dynamics) it is a good idea to first check out this post: 2. What is MOND?

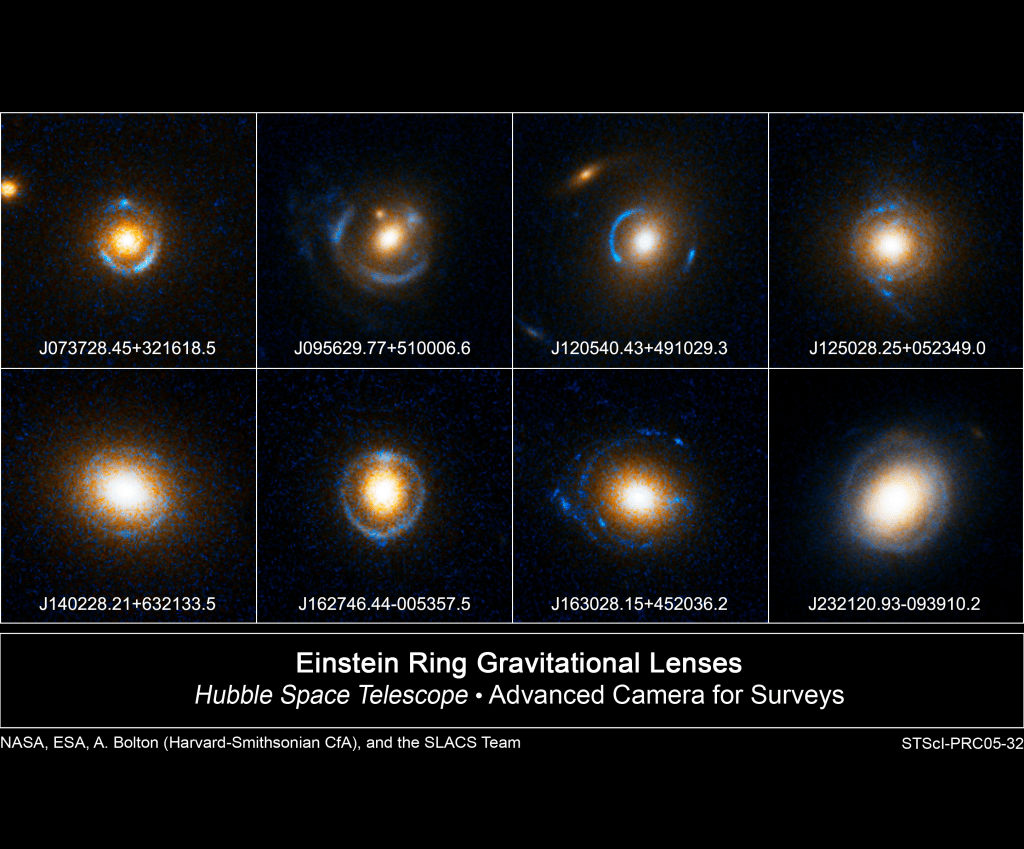

As mentioned in the previous post on the Bullet Cluster, the challenges posed by galaxy clusters extend beyond that particular example—none of them align well with MOND. By analyzing the starlight and gas density (inferred from X-ray emissions), we can estimate the ordinary mass in galaxy clusters (stars and gas combined). Then, using the hydrostatic equilibrium equation and reasonable assumptions about the gas temperature, we can calculate the cluster’s dynamical mass. This process is directly analogous to examining gravity in spiral galaxies by comparing the visible mass to the motion of stars.

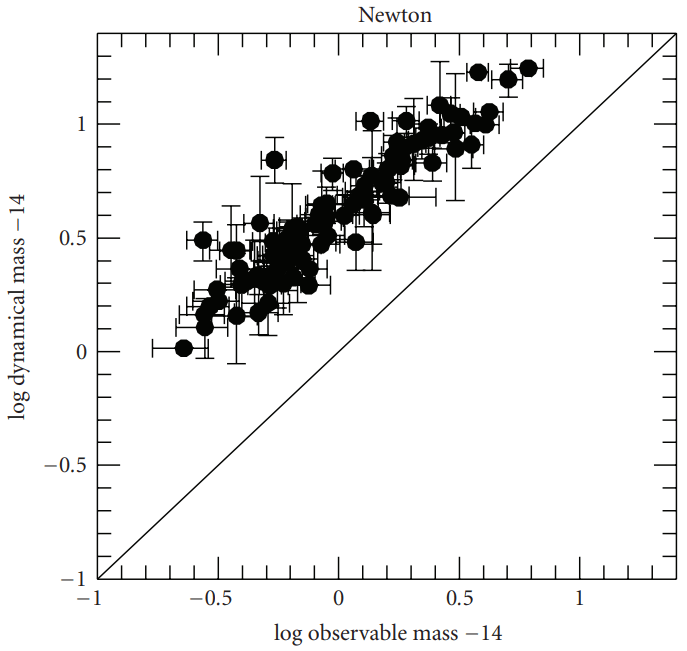

The issue is illustrated in the two graphs below. The left-hand graph presents the data under Newtonian dynamics, while the right-hand graph does so under MOND. In MOND we would expect the data to drop down to the line of unity, eliminating the need for dark matter. However, as shown in the second plot, MOND significantly reduces—but does not fully eliminate—the need for dark matter. Worse the scatter in the data increases.

This issue has been recognized for decades and is widely regarded as the most significant challenge to MOND. While other datasets, such as the power spectrum and polarization of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), are also critical, they typically require relativistic analysis—an area where MOND does not offer specific predictions. Galaxy clusters, by contrast, are classical systems where MOND should, in principle, provide accurate predictions given the gravitational field strengths involved. Yet, across the board, MOND’s predictions fail to align with observations.

If MOND cannot eliminate the need for dark matter in galaxy clusters, this is a strike against the theory. Proposing new particles or new laws of nature is a speculative endeavor, but needing to propose both simultaneously stretches plausibility even further. Thus this persistent mismatch has been aptly dubbed the “MOND Cluster Conundrum” in the literature.

MOND falsified?

Perhaps galaxy clusters falsify MOND entirely, suggesting it’s time to abandon the theory. But let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. This is very much an area of active research, and in the rest of this post, I aim to make the case that MOND is still plausibly correct.

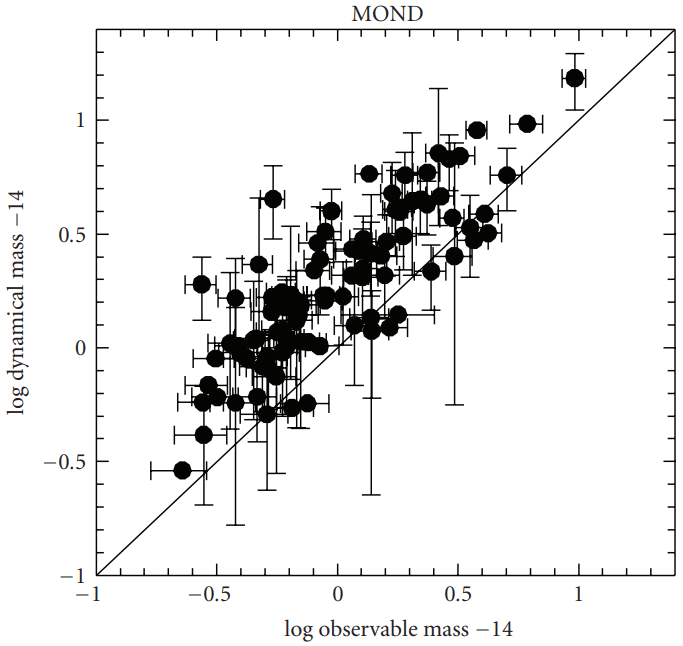

The cluster conundrum likely stems from flawed analysis methods for X-ray-emitting systems and MOND itself hints at this, much like in this post. To get an initial sense of why this might be the case, take a look at the following plot:

It is curious that dwarf galaxies, gas dominated spiral galaxies and star dominated spiral galaxies (lower left)adhere closely to MOND’s predictions. Yet, when we turn to systems with significant amounts of hot, X-ray-emitting gas, the data suddenly diverge. Interestingly, despite this discrepancy, the slope of the data still aligns with MOND’s expectations.

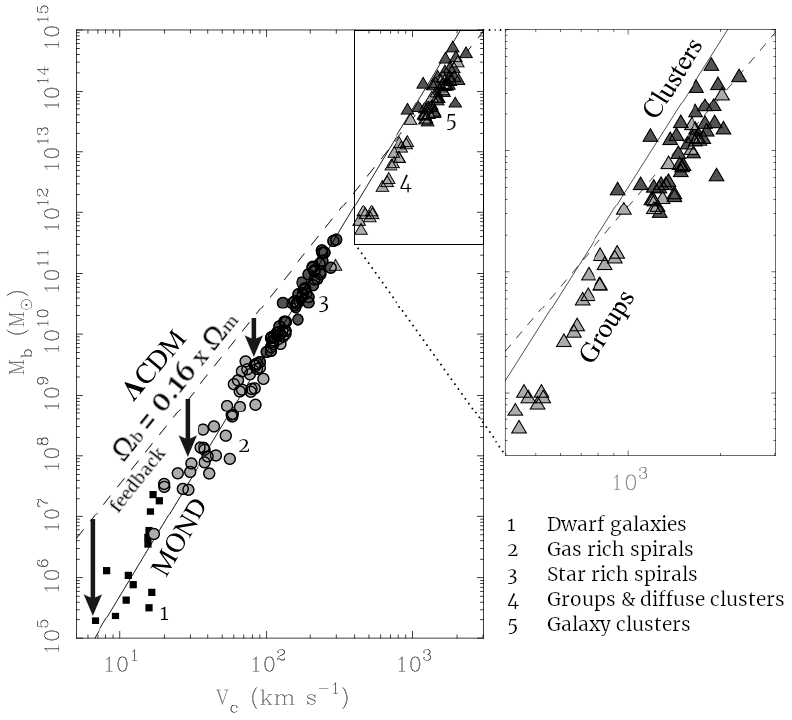

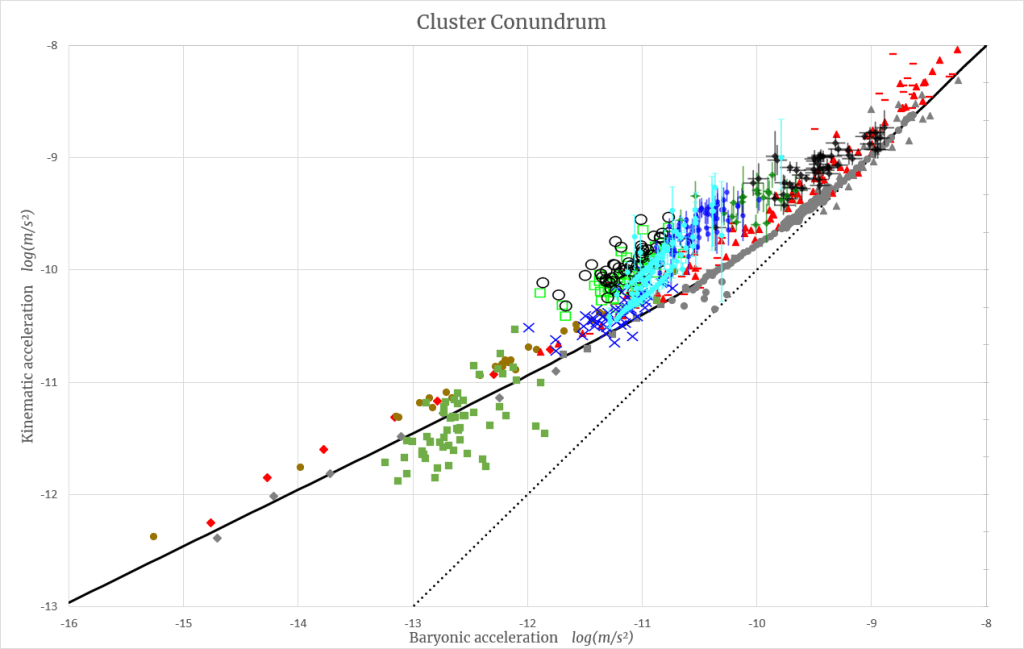

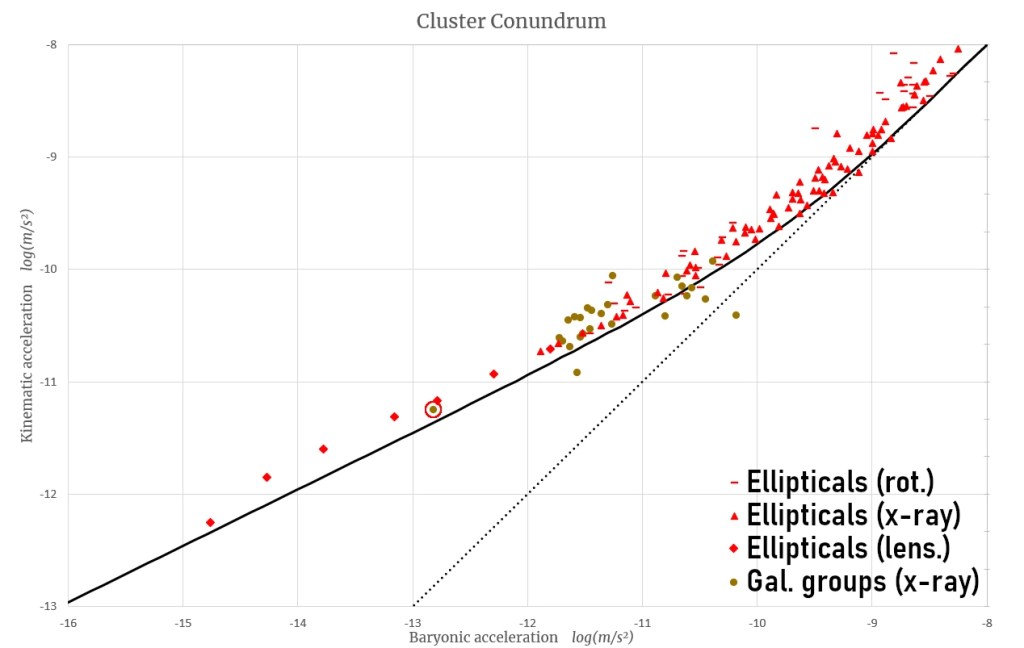

In the remainder of this post, we’ll delve into the plot below. It presents a dense, seemingly impenetrable forest of data—the observational foundation of our analysis. We’ll disentangle it step by step as we proceed. For now, take a moment to observe the overall pattern. True, the data doesn’t align with the black Milgromian prediction line, nor does it scatter around it.

If dark matter were the sole explanation, the data could theoretically scatter anywhere above the dotted black line, which represents the Newtonian prediction based solely on visible, ordinary mass. Yet, intriguingly, most of the data collectively forms a band with the same shape as MOND’s prediction—albeit shifted slightly upward.

So let’s dissect all of this data by looking at groups of similar datasets. We shall see that there are regularities to be had here that point us to a resolution of the cluster conundrum.

Are large systems different?

A first obvious thought as to why clusters behave differently than MOND is that size matters. Clusters are big. Much bigger than galaxies. However, when examining datasets on size scales comparable to clusters, we don’t observe the same offset. For instance weak lensing around spiral galaxies by Brouwer et al. (2021) has been done at extreme distances, reaching scales similar to clusters. Additionally Milgrom (2019) has studied high quality galaxy groups devoid of X-ray emitting gas. These groups are also the same size as clusters, albeit less massive. Neither the weak lensing nor the high quality galaxy groups exhibit the same missing mass problem as clusters.

In fact, these groups even fall ever so slightly below the MOND expectation on average and more so towards the low acceleration end of the data. Since the line in the plot below represents the expectation for fully isolated systems these galaxy groups even afford a test of the MOND external field effect. By including a small external field—on the order of 10-14 m/s2 —these groups scatter neatly around the expectation. This is a reasonable value, consistent with the influence of the large scale structure of the universe.

Are spherical systems different?

Milgrom’s galaxy group sample also demonstrates that sperical systems (“pressure supported systems”) do not, in general, exhibit the cluster conundrum. Note that this sample was deliberately chosen to exclude systems with hot, X-ray-emitting gas.

Further evidence against sphericity being the issue comes from globular cluster systems within the local group. These ancient balls of stars adhere closely to MOND’s predictions, remaining on the expected line in the Newtonian regime (a>a0).

Similarly, dwarf spheroidal satellite galaxies of the Milky Way and Andromeda also align with MOND expectations. However, these systems are subject to strong external fields compared to their internal gravity, necessitating consideration of both the external field effect and tidal forces. This more complex scenario warrants a deeper dive, which will be the focus of a separate post:

Do dwarf galaxies disprove MOND?

Elliptical galaxies as mini-clusters

Having discussed spiral galaxies, galaxy groups, globular clusters, and dwarf satellite galaxies, let’s now turn to elliptical galaxies—giant spheres of stars and hot, X-ray-emitting gas. Elliptical galaxies provide data spanning an impressive seven orders of magnitude in baryonic acceleration, rivaling spiral galaxies. These systems have been studied through several complementary methods, including weak lensing by Brouwer et al. (2021) and rotation curves, and X-ray hydrostatic equilibrium analyses by Lelli et al. (2017). We can clearly see MOND is at work here.

In particular look at the galaxy groups containing hot xray gas as studied by Angus et al. (2008), included in brown on the plot. The lower-mass end of these systems begins at the elliptical galaxy level, with one notable example—a galaxy group that is essentially an elliptical galaxy with dwarf satellites—highlighted by the red circle. The data reveal a clear continuity, spanning from small elliptical galaxies with dwarf satellites to large galaxy groups.

In the plot above, I’ve assumed the same constant mass-to-light ratio for ellipticals as for spiral galaxies (M/L=0.5 in the 3.6micron or the K-band). A higher mass-to-light ratio of M/L=0.8 shifts all the red data points to the right, aligning them with the MOND expectation.

Since almost all the data were acquired using infrared photometry, which permits color-independent mass-to-light ratios, it seems reasonable to apply a constant M/L across the entire category. Similarly, it may make sense to use the same M/L for both spirals and ellipticals.

This analysis offers a subtle hint that elliptical galaxies—though much smaller than galaxy clusters but still containing hot, X-ray-emitting gas—exhibit the cluster conundrum or otherwise require a slightly higher mass-to-light ratio than disk galaxies. Now this could be due to a different distribution of star types (“a different population”) causing a higher M/L than in spirals. On this topic, Professor Stacy McGaugh provides and interesting perspective:

As for an offset between ellipticals and spirals – could be. There are persistent indications to that effect. The E & S0 galaxies we analyzed in Lelli et al (2017) were consistent with the RAR if their stellar mass-to-light ratios were higher than those of spirals. I forget the shift now – it wasn’t a factor of two, but it wasn’t too far shy of that either. That could just be a population effect, or it could be a systematic offset. I think one could argue it either way: it was clear enough that there had to be some shift, but nothing so large that it couldn’t just be a population difference.

If elliptical galaxies indeed host slightly different stellar populations and exhibit a higher mass-to-light ratio, they may not be relevant examples of the cluster conundrum. This would disrupt the continuity observed with the galaxy group dataset, as well as challenge the idea that the division in the data aligns neatly with the presence or absence of hot, X-ray-emitting gas.

Could elliptical galaxies, then, simply be mini-clusters, exhibiting a smaller-scale version of the same issues seen in full-fledged galaxy clusters? To address this possibility, let’s turn our attention to the actual clusters next.

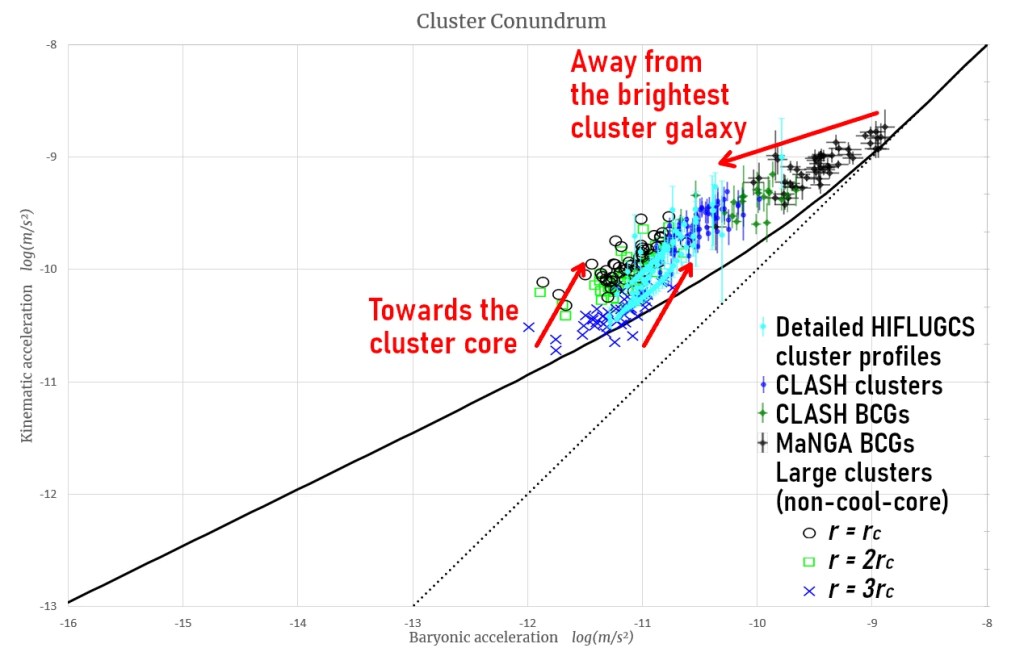

Galaxy clusters examined

Let’s get to the heart of the matter. The graph above presents five recent datasets on galaxy clusters. While more data are available showing similar trends, including them would have rendered the graph unreadable.

The cyan points represent detailed radial profiles of clusters from the HIFLUGCS sample (Li et al. 2023). Two additional studies, based on CLASH (Tian et al. 2020) and MaNGA (Tian, 2021) focused on the brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs)—massive elliptical galaxies typically found at the centers of most clusters. The final dataset (Chan & Del Popolo, 2020) examined several clusters at three specific radii. These radii are defined as multiples of the radius where the cluster’s mass density equals the critical density of the universe, allowing for fair comparisons across clusters.

As shown in the graph, the mismatch with MOND predictions is not constant. At larger radii, the discrepancy diminishes, but it increases significantly toward the core of the cluster. Interestingly, BCGs appear to be less affected, with the mismatch growing as the sampled region encompasses less of the BCG itself and more of the surrounding intracluster medium.

This pattern suggests that potential depth is unlikely to play a role in resolving the cluster conundrum. Since BCGs are far denser than the surrounding intracluster medium, they represent the deepest part of the cluster’s gravitational potential. If gravitational potential were a factor, we would expect the discrepancy to increase with the BCG fraction. Instead, we observe the opposite.

When measuring the core of the intracluster medium using X-ray hydrostatic equilibrium, the mismatch is most pronounced—off the MOND prediction by a factor of 2–3.

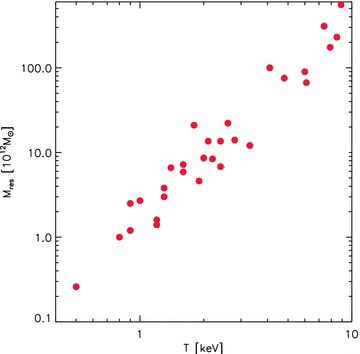

Furthermore, there is a strong correlation between the gas temperature and the residual mass required after accounting for the deduced mass of the X-ray gas and the BCG:

Additionally the data on galaxy clusters also shows that a separate a0 for clusters does not fit the data since the data has a clear bend which a mere change of a0 cannot replicate. That explanation is also disfavoured by ellipticals because they run parallel to the Newtonian expectation at the high acceleration end.

Finally additional baryonic components like Milgrom’s cold dense clouds (Cluster Baryonic Dark Matter, CBDM) are unlikely because they would likely form out of cooling flows and cause a lot of star formation which is not observed. See the defining review by Fabian (1994) and this more recent one by McDonald et al. (2018).

Regularities

All of the observations above can be summarised in a number of regularities that describe the cluster conundrum:

- If there is no hot X-ray gas, there is no discrepancy—and vice versa.

- The higher the ratio of baryons in hot X-ray gas to those in stars, the larger the discrepancy.

- The greater the total mass of the X-ray gas, the greater the discrepancy.

- The closer to the core of the hot X-ray gas, the greater the discrepancy.

- The higher the X-ray temperature, the greater the discrepancy.

Speculation time!

Assuming no significant population difference between spiral and elliptical galaxies, the observed discrepancies occur exclusively in systems with hot, X-ray-emitting gas, and occur in all such systems. The discrepancies further scale with the density of that gas. This might suggest a flaw in X-ray analysis techniques. However, the data supporting these observations come from over a dozen independent studies, conducted by various authors and observatories, making a widespread implementation error unlikely.

Instead, the issue may lie in a fundamental assumption common to all X-ray analysis methods. To investigate this possibility, let’s briefly review the theory behind X-ray analysis and consider an example of a potentially faulty underlying assumption.

X-ray analysis basics

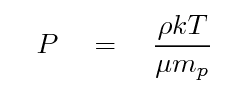

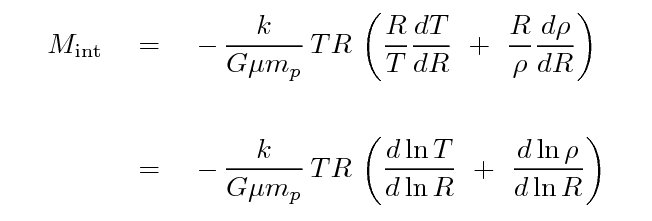

The analysis of X-ray systems assumes the hot gas behaves as an ideal gas, enabling the use of the following equations:

Here P is the pressure, ρ is the density of the gas, T is temperature, k is Boltzmann’s constant, μ is the mean molecular weight of the gas, and mp is the mass of the proton. This pressure can then be coupled to gravity through Newton’s law:

By further assuming the gas is in hydrostatic equilibrium (neither contracting or expanding) the following expression for the mass enclosed within a certain radius can be derived:

A further simplification often applied is the beta model, which assumes the gas is an isothermal sphere. While convenient for lower-resolution observations, this model makes strong assumptions that may not hold universally.

After determining the baryonic mass profile (stars + X-ray gas), it is compared to the dynamically observed mass profile derived from galaxy velocity dispersions or gravitational lensing. In high-quality studies, stellar mass is included but typically contributes only about 20% or less of the total baryonic mass.

Unaccounted-for pressure

All these methods assume the hot X-ray gas and gravity are the sole contributors to the observed dynamics. But what if an additional source of pressure exists? If the left-hand side of the second equation above increases due to unaccounted-for pressure, we would infer a higher total mass. This could, in principle, resolve the Cluster Conundrum if the additional pressure is distributed appropriately.

One plausible candidate is the non-thermal pressure from ultra-relativistic electrons. These electrons are accelerated to near-light speeds during cluster formation and, while contributing little mass, exert significant pressure. Such electrons are observed through their radio emissions, which form diffuse halos at ~100 MHz and concentrated features called “relics” at GHz frequencies.

These radio halos often reside in cluster cores, qualitatively matching the areas where the Cluster Conundrum is most pronounced. This non-thermal pressure is inherent to the X-ray emitting gas explaining why there are no systems without such gas showing the Cluster Conundrum discrepancies. Furthermore, clusters with higher X-ray temperatures—indicative of more violent formation—tend to exhibit greater mass discrepancies, aligning with the idea that more energetic electrons generate more non-thermal pressure.

Quantifying Non-Thermal Pressure

To date, no MOND-based study has included non-thermal pressure from ultra-relativistic electrons when analyzing clusters. This pressure is often estimated as ~15% of the total based on ΛCDM, assuming clusters conform to the cosmic baryon fraction at R500. See for example Ettori and Eckert (2022). However, these estimates rely on assumptions rooted in dark matter models, which MOND does not share.

For example the use of constant baryon-to-dark matter ratios is problematic from a MOND perspective, as it effectively assumes a fixed value of the interpolation function irrespective of the local gravitational acceleration. This assumption contradicts MOND’s framework, where the interpolation function varies with the gravitational field strength. As an alternative to the use of a constant baryon-to-dark matter ratio, ΛCDM analyses often incorporate poorly constrained feedback factors to adjust baryon-to-dark matter ratios. While these adjustments aim to account for variations in baryon distributions, they similarly imply values of the MOND interpolation function inconsistent with local gravitational conditions. Compounding the issue, these methods often neglect direct observational constraints from radio data, which could reveal the true pressure exerted by non-thermal electrons. Radio halos and relics, which trace ultra-relativistic electron populations, provide an observationally grounded means of estimating the additional pressure.

A rigorous MOND analysis would need to incorporate both MHz and GHz observations of the electron spectrum to account for the steep decline in electron energy distribution in a joint fit with X-ray data. As Harris et al. (2019) noted:

To compute the minimum energy and pressure in nonthermal plasmas, the most conservative approach is to integrate the electron spectrum only over those energies producing observable emission. However, because of the steepness of the electron spectrum, it is often the case that most of the total energy resides in the lowest energies, so when these are ignored, we introduce significant uncertainties into our estimates of the magnetic and electric fields, and the pressure contribution of the nonthermal plasma, etc. Obtaining radio spectra to low frequencies will significantly reduce these uncertainties.

In other words without data in the MHz range (such as the new data from LOFAR for example) there really is no telling whether this source of pressure is sufficient to solve the Cluster Conundrum or not.

Revisiting the Bullet Cluster

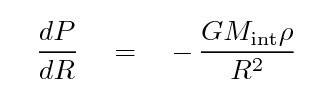

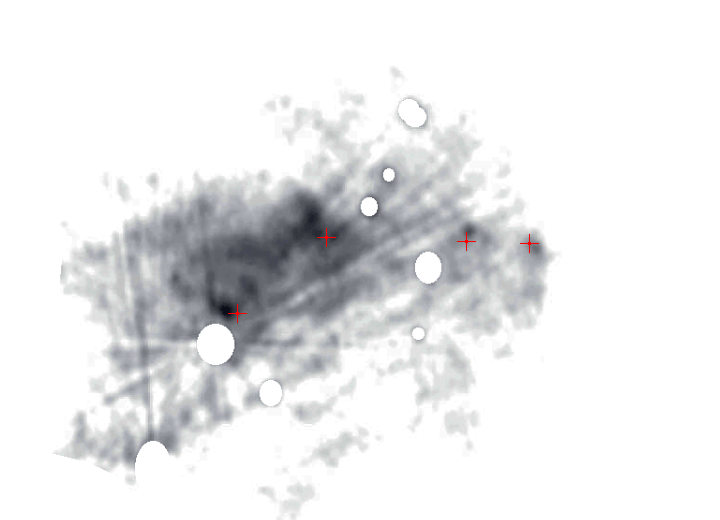

Intriguingly, the Bullet Cluster provides indirect evidence that non-thermal pressure from ultra-relativistic electrons may be the key to the Cluster Conundrum. As discussed in the previous post, MOND predicts additional mass in four distinct regions of the Bullet Cluster, based on work by Angus, et al. (2007):

Subsequent radio observations by Shimwell, et al. (2014) mapped the cluster’s radio halo at 1.1–3.1 GHz. These observations revealed peaks in ultra-relativistic electron concentrations at precisely the locations where MOND predicts missing mass or pressure(marked by red crosses in the map above and below).

The pattern matches the MOND prediction. There are four peaks in the concentration where MOND expects them to be.

Notably, the MOND prediction predates the radio observations by eight years, making this a true a priori scientific prediction. While Angus et al. interpreted the missing mass as hypothetical sterile neutrinos, the alignment with radio halo peaks suggests the true explanation could lie in unaccounted-for non-thermal pressure.

A further check based on xray temperature

If the hypothesis about nonthermal pressure presented here is correct, we might make a further deduction. Examining the radio halo image above in conjunction with the previous analysis of the Bullet Cluster, we notice that the rightmost region where MOND identifies an anomaly appears relatively small in the radio halo. This may be an artifact related to the X-ray temperature.

In less energetic regions, where less energy is available to accelerate electrons to relativistic speeds, we would expect nonthermal pressure to be lower. Figure 5b of Shimwell supports this notion, showing a dramatic drop in X-ray temperature toward the right side of the Bullet Cluster. Consequently, the radio emissions used to map the halo would shift to lower frequencies in these cooler areas. If this reasoning is correct, the rightmost peak should be more prominent in a less energetic radio band, such as the 100 MHz range, compared to the GHz range.

Summary

The Cluster Conundrum is a longstanding problem for MOND. This post has summarised the current data into several observed regularities. These are:

- If there is no hot X-ray gas, there is no discrepancy—and vice versa.

- The higher the ratio of baryons in hot X-ray gas to those in stars, the larger the discrepancy.

- The greater the total mass of the X-ray gas, the greater the discrepancy.

- The closer to the core of the hot X-ray gas, the greater the discrepancy.

- The higher the X-ray temperature, the greater the discrepancy.

This post has further provided evidence against various proposed solutions to the Cluster Conundrum:

- Size, ruled out by weak lensing and X-ray free galaxy groups.

- Pressure support, ruled out by X-ray free galaxy groups, globular clusters and dwarf galaxies.

- Different a0 for clusters, ruled out by the shape of the scatter.

- Potential depth, ruled out by brightest central galaxies

- Sterile neutrinos, unobserved hypothetical particle and does not explain elliptical galaxies

- Cold dense clouds, unlikely given the absence of cooling flows and high star formation

A potential qualitative solution that does seem to fit all available data is proposed however: the presence of unaccounted nonthermal pressure from ultra-relativistic electrons, as evidenced by radio halos. This idea gains further support from the example of the Bullet Cluster, where the observed radio halo aligns qualitatively with MOND’s a priori expectation—though no quantitative study has yet been conducted.

What’s next?

A lot of further research is required. Are the regularities described here universally valid, or do exceptions exist? Is the additional nonthermal pressure from electrons quantitatively sufficient to solve the conundrum, or are alternative explanations—such as additional baryonic components like Milgrom’s cold dense clouds (Cluster Baryonic Dark Matter, CBDM)—necessary? Do sterile neutrinos exist, and could they play a role? Could a superfluid dark matter theory that mimics MOND provide the ultimate solution? Time will tell.

References

Angus, G. W., Shan, H. Y., Zhao, H. S., & Famaey, B. (2007). On the Proof of Dark Matter, the Law of Gravity and the Mass of Neutrinos. In The Astrophysical Journal (Vol. 654).

Angus, G. W., Famaey, B., & Buote, D. A. (2008). X-ray group and cluster mass profiles in MOND: Unexplained mass on the group scale. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 387(4), 1470–1480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13353.x

Chan, M. H., & del Popolo, A. (2020). The radial acceleration relation in galaxy clusters. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 492(4), 5865–5869. https://doi.org/10.1093/MNRAS/STAA225

Ettori, S., & Eckert, D. (2022). Tracing the non-thermal pressure and hydrostatic bias in galaxy clusters. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 657. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202142638

Fabian, A. C. (1994). Cooling Flows in Clusters of Galaxies. Annual Review Of Astronomy And Astrophysics, 32(1), 277–318. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.aa.32.090194.001425

Harris, D. E., Moldón, J., Oonk, J. R. R., Massaro, F., Paggi, A., Deller, A., Godfrey, L., Morganti, R., & Jorstad, S. G. (2019). LOFAR Observations of 4C+19.44: On the Discovery of Low-frequency Spectral Curvature in Relativistic Jet Knots. The Astrophysical Journal, 873(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab01ff

Li, P., Tian, Y., Júlio, M. P., Pawlowski, M. S., Lelli, F., McGaugh, S. S., Schombert, J. M., Read, J. I., Yu, P. C., & Ko, C. M. (2023). Measuring galaxy cluster mass profiles into the low-acceleration regime with galaxy kinematics. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 677. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346431

McDonald, M., Gaspari, M., McNamara, B. R., & Tremblay, G. R. (2018). Revisiting the Cooling Flow Problem in Galaxies, Groups, and Clusters of Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal, 858(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aabace

Pfrommer, C. (2015). The Physics of Galaxy Clusters.

Shimwell, T. W., Brown, S., Feain, I. J., Feretti, L., Gaensler, B. M., & Lage, C. (2014). Deep radio observations of the radio halo of the bullet cluster 1E 0657-55.8. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 440(4), 2901–2915. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stu467

Tian, Y., Cheng, H., McGaugh, S. S., Ko, C.-M., & Hsu, Y.-H. (2021). Mass–Velocity Dispersion Relation in MaNGA Brightest Cluster Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 917(2), L24. https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ac1a18

Tian, Y., Umetsu, K., Ko, C.-M., Donahue, M., & Chiu, I.-N. (2020). The Radial Acceleration Relation in CLASH Galaxy Clusters. The Astrophysical Journal, 896(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab8e3d

Leave a reply to Maarten Havinga Cancel reply